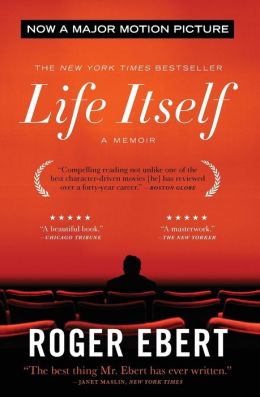

Last year I picked up Roger Ebert's memoir Life Itself, which had been recently released on paperback, and have read a chapter or two of it before bed many nights the last few months. In a way, I feel guilty to admit it, but I kind of figured that, slow reader that I am, there was a good chance he'd be dead by the time I finished the book, and it'd be a book I'd definitely want to read at that point. It's really a lovely read, though, I'm glad I have it, especially this week, when he finally did pass, after a decade of publicly struggling with the physical effects of cancer while remaining not only mentally sound but becoming a better and more prolific writer.

Anyone who survives that long with that kind of illness is admirable, but there was something almost wonderfully defiant about how, having been diagnosed not long after cancer took his old co-star Gene Siskel's life in a matter of months, Ebert just kept going. Last year he reviewed 300 movies, the most in his whole 46-year career.

One of the many remembrances of Ebert written this week was by Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, the co-host of the short-lived reboot of "At The Movies" that I found pretty enjoyable even without Ebert's onscreen presence. Vishnevetsky only knew Ebert in his frail final years, and at one point notes how slowly Ebert typed, sometimes as slow as thirty seconds per sentence. Reading that kind of stopped me in my tracks. I had assumed, given his voluminous recent output, that his fingers where still in good enough shape to type 80 words per minute (and of course, Vishnevetsky was referring to how Ebert typed on the apparatus that 'spoke' for him -- perhaps at a laptop he was a bit faster).

That he was writing so much, so well, when even the physical act of writing was slow and difficult, is just amazing. But towards the end, that was one of the only things he had left. And he made the most of it. I've had the thought, many times, that I am prepared for whatever physical challenges old age brings me, as long as I have my mental facilities, and am able to read and write, and keep stimulating my mind and communicating with people. Ebert's final years were like an embodiment of that idea, and a strangely reassuring one to me. He wrote a lot, sometimes well, sometimes not so well, but always honestly and with thought and effort. One of the most bizarre things he ever penned, a positive review of Garfield: A Tale Of Two Kitties written from the perspective of the animated cat himself, was published on the day he underwent the surgery to remove his jaw and permanently take way his ability to speak.

Ebert is, of course, a touchstone for any critic of any kind, even if he kind of fell into film criticism; he grew up loving words and wanting to be a newspaperman, but 'film critic' was kind of a nascent, undignified profession when he was assigned the beat. It's something of luck and timing that he was so good at it, and that he and another not especially photogenic man became the trade's television celebrity representatives. But what's remarkable is how much he continued to devote himself to writing, even after it would've been easy to bring in easy TV money. Think of how few writers, in any medium, have or would stay so dedicated to the word processor even after becoming regulars on the talk show circuit.

And again, his longevity and stamina as a writer, in addition to the eloquence and humor and humanity in his writing, are a huge inspiration to me. Writing is not something everyone enjoys or excels at doing, but it unites nearly all of us. And it feels almost absurd to be able to make a living at it, the same way some people would feel about getting paid to play video games or walk their dog or something. But again, it's something that should be consistent throughout your adult life. And while we're used to the idea of an artist, say a novelist who writes some masterpieces and then spends his later years stuck in writer's block, laboring over a follow-up, or a newspaper hack heartlessly churning out copy for a paycheck until the day he dies, Ebert showed another way. A way to dedicate yourself to a type of writing for decades, while constantly expanding your subject matter, drawing readers more and more into your own world while ostensibly informing them about something else entirely.

One of the reasons I loved Roger Ebert is that he was a great practitioner of negative reviews, which are the main reason critics are often looked at as cranky takedown artists, but are simply a necessity of the job. I'm a huge fan of his book I Hated, Hated, HATED This Movie; I actually saw the original airing of the infamous Siskel & Ebert episode in which they reviewed North, the movie that inspired the books title. On my Twitter, I quoted some of his greatest pans under the hashtag #EbertEther. I'm primarily a music critic, but on the couple dozen occasions my paper had me review movies, I can only hope did it half as well as he did. And no matter what medium I'm reviewing, I aspire to his mastery of tone, his balance of humor and respect for the artform, his social conscience and his love of every experience, even the worst art he ever had to sit through.

Post a Comment